How the Confederacy Lost the Civil War but Won the Narrative

Part 2: Power & Memory

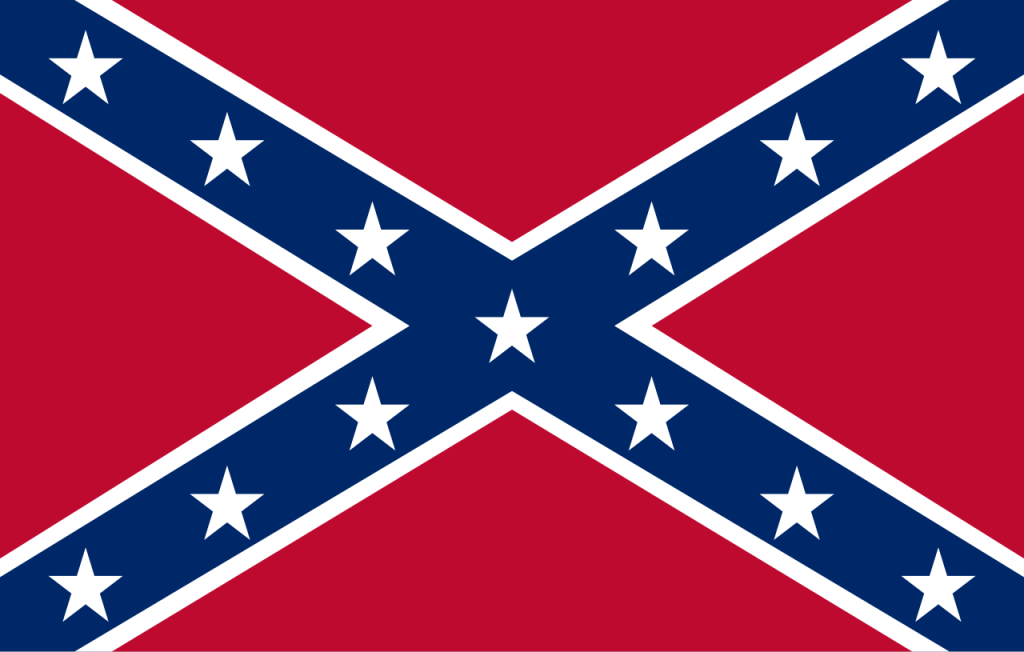

In the first installment of this series, we examined how authority determines what is preserved, emphasized, and obscured in the historical record. This essay turns to a more unsettling question: What happens when those who lose a definitive war retain the institutional capacity to define its meaning? The history of Confederate commemoration demonstrates that military defeat does not automatically translate into narrative displacement. It reveals how institutions, political coalitions, and public memory can survive the outcomes of the battlefield.

Whoever said that history is written by the victors never considered the aftermath of the American Civil War. Beginning with the attack on Fort Sumter in April 1861 and ending with the surrender of Confederate General Robert E. Lee at Appomattox Court House in April 1865, the Civil War was the deadliest conflict in American history. Between 620,000 and 750,000 soldiers died in the conflict—more American fatalities than in all other U.S. wars of the nineteenth century combined. Of those dead, approximately 360,000 were Union soldiers and roughly 260,000 were Confederates. The demographic consequences for the South were catastrophic: historians estimate that nearly one in four military-age white men in the Confederacy perished. Entire towns lost a generation. Infrastructure lay in ruins. The Confederate government ceased to exist.

The losses fell heavily on the Confederacy. By every measurable standard imaginable — military, political, and economic — the Confederacy was defeated by the better-equipped Union forces.

The phrase that insists that the victors write history persists because it appears to describe a rule of power. Armies that prevail secure territory and authority. Governments that survive shape textbooks, monuments, and civic celebrations. The narrative of victory becomes a permanent fixture in the public memory of Americans.

Yet its definitive defeat did not extinguish its ideology. Following the Civil War, the South complicates the belief about who gets to record what occurred in the pages of history books.

In 1865, the Confederate States of America collapsed. Its political experiment ended. Its armies surrendered. It failed in its explicit objective: the preservation and expansion of slavery. Once again, by any conventional measure, the South were indeed the losers.

Despite their obvious defeat, they erected monuments to celebrate Confederate traitors decades later.

This excerpt is from our essay for Remnants, an online project that investigates how power, history, and memory shape the American present. Read the complete essay on Substack at this link.